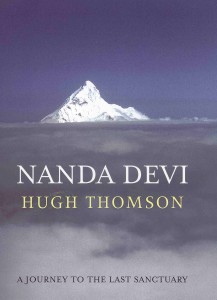

Nanda Devi:

Nanda Devi:

High heaven: a trek to the top of the world

The Nanda Devi Sanctuary is even more difficult to reach than the North Pole, but this Himalayan mountain valley has lured explorers for centuries. Hugh Thomson describes his daring ascent to paradise

08 April 2004

Imagine one of the tallest mountains in the world. A high and beautiful valley curls around it like a moat, filled with rare flowers and wildlife. Now imagine also that around this valley is a ring of Himalayan tooth-edged peaks, linked to each other by an impenetrable curtain of cliffs, forming a protective guard for the mountain at their centre. Then circle this protective wall with another "moat" and another high wall of peaks, so that there is both an inner and outer keep, like the fortifications of a medieval castle. Allow just one entrance to the valley sanctuary at the heart of this complex - a river gorge that drains the mountains' glaciers and cuts through the curtain walls with a chasm of such breathtaking steepness and ferocity that in the past even hardened climbers have turned away from it in despair.

In some ways it is easy to imagine such a place - because literature has already pictured it, many times. The idea of the "sanctuary", the earthly paradise, is as old as Eden and is common to both Western and Eastern religions. More recently, Hollywood has perpetuated it as a "Shangri-La" which explorers try to reach at their peril.

But such a place exists in reality. It is called the Nanda Devi Sanctuary, in the Himalayas between India and Tibet. And the torrent which issues from its formidable gates is one of the sources of the Ganges, perhaps the world's most revered river. The often tragic history of those who have tried to reach it shows what happens when the dream of finding a sanctuary, one of mankind's oldest and most compulsive quests, collides with solid rock. In the past, Nanda Devi has claimed many lives.

For many years it has been closed to all outsiders because of its position on the border with Tibet; such complete inaccessibility has only increased its appeal. So when the opportunity of a lifetime came up - the last place on what could well be the only expedition ever allowed back there - I grabbed it with both hands, despite the fact that my background was in exploration, not mountaineering. "Never mind," said the expedition organiser, Steve Berry, "as long as you've got a good head for heights, you'll be fine." As I was later to discover, this was in the "if you can manage a length in the pool, you can swim the Channel" league of understatement.

As soon as I arrived in Delhi, I went to see Bill Aitken. I'd first met Bill when I was travelling the Hindu pilgrimage route through the Himalayas, and had immediately taken to his mixture of Indian inclusiveness and Calvinist rigour. He was one of the few people I knew who had ever reached Nanda Devi. I had already rung him before leaving England for advice. He had given no guidance of any practical use whatsoever, but had simply said: "In climbing to the Sanctuary, it helps to have a belief in something, anything, that endures."

He was waiting for me at the door of his house in Delhi, his intense blue eyes peering out beneath a Himachal Pradesh hat perched jauntily on cropped silver hair. Bill was a maverick. He described himself as "Scottish by birth, naturalised Indian by choice." He had hitchhiked to India in 1959 to live in an ashram. After some years, he had, in his words, "escaped" the ashram, together with Prithvi, his future wife, and they had happily wandered the subcontinent ever since. "Of course," said Bill, "the amusing thing about the Empire attitude was the idea that we started the idea of hill stations where we could aestivate, and cut the summer heat. But in actual fact it was the Hindu gods who started this notion of wintering in the lower regions and spending the summer in the snowy heights. Long before the Alpine Club was founded, the Hindu gods - and goddesses - had cottoned on to the idea that mountains were a wonderful place to be in hot weather."

A few early colonial adventurers managed to climb the high peaks that made up the "inner wall" around Nanda Devi, but they could only look down with longing at the Sanctuary below; the cliff walls fell away with such ferocity that even today, no one has ever descended them.

Nanda Devi quickly became one of the great mountaineering goals, and for one simple reason: at 25,640 feet high, it was not only the highest mountain in India, but the highest mountain in the British Empire. Yet no one could even get to its base. For almost a century the Alpine Club puzzled over the conundrum of how to enter the elusive Sanctuary. The best of three generations of climbers all made the attempt and failed.

As Bill reminded me, there had been no fewer than eight attempts to get inside. Each expedition had demanded a long trek in over the foothills and a complicated circumnavigation of the enormous Nanda Devi massif, which the Everest veteran Hugh Ruttledge described as "a 70-mile barrier ring, on which stand 12 measured peaks over 21,000 feet high. The Rishi Ganges gorge, rising at the foot of Nanda Devi, and draining an area of some 250 square miles of snow and ice, has carved for itself what must be one of the terrific gorges in the world." This made the Sanctuary, said Ruttledge, "more inaccessible than the North Pole".

It was left to two mavericks, Eric Shipton and HW Tilman, to pull off one of the most audacious of mountaineering coups. When they went to Nanda Devi in 1934, Shipton was just 26, Tilman some 10 years older. Temperamentally, Shipton and Tilman could not have been more different: Shipton belonged to the Twenties and Thirties set for whom experimentation in travel, sex and literature was natural; by comparison Tilman was of the older generation who had fought in the First World War, a man of few words and fixed ideas. But whatever their differences, they formed one of the most effective exploring combinations of all time. They refused to be beaten by the terrors of the gorge during the months of their assault on it.

Going completely against the custom of the time, Shipton and Tilman avoided the usual large military-style expeditions, with endless porters and a string of base-camps, considered to be the only way to "conquer" such peaks. Instead the two set off alone, with just a shirt each, intending to live off the land. They relied on the skills and instincts of a few hand-picked Sherpas and shared all they had with them.

Even after all these years, the account left by Shipton and Tilman of the Sanctuary was an enticing one: they spoke of blue sheep grazing in the high pastures, unafraid of man, of snow leopards and of a natural wildlife sanctuary in a cirque of beautiful mountains. It was a prelapsarian vision.

Bill had been one of the last people to reach the Sanctuary before it was closed by the Indian government some 20 years before. Ever since, it had been an inaccessible place, a legend whose appeal had grown precisely because, in a world where seemingly everywhere is open to the traveller, Nanda Devi was closed. Until now.

"And how," asked Bill, "have you managed to get in?" "Because the expedition is being led by John Shipton and 'Bull' Kumar," I said. John Shipton was Eric Shipton's son. And "Bull" Kumar was probably India's most famous living mountaineer. He had led the first Indian team to climb Nanda Devi in 1964, only the second successful attempt after Tilman's. It had needed a dream ticket like that to persuade a reluctant Indian government to let us in.

I found myself remembering that conversation with Bill many times in the long weeks ahead as we made our way into the mountains. Increasingly, what interests me on such journeys of exploration - be they for Inca ruins or for mountains - is the difference between the myth engendered by a place and what you actually find.

There is a Buddhist tradition of sacred texts called terma being hidden in the mountains by sages for later generations to rediscover, and, as we travelled, I found that for a supposedly unoccupied area there seemed to be a surprising number of hidden stories in the Sanctuary. Strange CIA plots to plant nuclear-powered devices so that they could spy on neighbouring China; the glacial remains of Buddhism itself as it had retreated through here on its way to Tibet; and, most resonant of all, the ghosts of those who had gone before, including the tragic figure of Nanda Devi Unsoeld, the young American climber named after the mountain, who had later died on it.

Indeed, the route was so extraordinary that now, when I look back, it hardly seems possible, a fantastical version of a Disneyland roller-coaster walk, but without the safety net. The route switch-backed up and down, over and around the huge buttresses. One moment you could be traversing around a cliff face on a ledge a foot wide, the next, climbing up stone slabs to reach the next crossing-place. And just when the path narrowed to nothing, a chimney would take you up or down to the fragile beginnings of another track. At any point in the expedition, our struggle to negotiate the terrain was played out with the noise of the river seemingly roaring for blood below, across the gorge. The equally sheer cliffs of the northern side stared at us blankly, an unfortunate reminder of what we ourselves were climbing along.

Once we got close to the difficult sections, Jeff and Barry reminded me of some basic mountaineering disciplines, some of which came back as a residual memory from messing around on climbing-walls years before. However, as the days wore on, my worries of the night before dispersed and I managed to find for myself that sense of detachment that Bull had once talked about. The fact that for hours we had a total exposure of a 3,000-feet drop beneath us as we made our way like flies along the side of the canyon walls became unreal. By focusing on the procedure for managing the fixed ropes and climbing the chimneys, I could ignore the vertiginous drops and overhangs. Shipton's and Tilman's achievement in finding their way through here in the first place was extraordinary.

A little further on, Albert had a nasty slip going round a fixed-rope section and fell. His carabiner held and he was left dangling over a 3,000-feet drop. With some difficulty, for Albert was not small, a nearby team member managed to pull the understandably shaken Yorkshireman back to safety.

Five of our party turned back, for reasons that I respected. The gorge more than lived up to my premonitions. But the company of high-octane mountaineers brought with it the occasional petrol whiffs of dissent and discord at times. More than anything, the ascent took its toll on our emotional fragility. Approaching the Sanctuary, I found I needed to reach deep to carry on. With the childishness that altitude exhaustion brings on, I found the competitive pleasure of being one of the front-runners of the group helped me. But all of my fears were vanquished as I finally got close to the narrow couloir (gully) that ascended up Pisgah, the last barrier to what Shipton had described as the "Promised Land" beyond.

The couloir was a narrow ascent to a cairn right at the top, traditionally known as "the Stairway to Heaven", because, as one porter told me, "It doesn't matter whether you climb it and reach the Sanctuary or whether you fall off: you will reach heaven either way."

But there was a final unexpected slip of the knot that released the noose; a ledge that led us off at an unexpected, oblique angle, followed by a steep climb. By this stage, adrenalin had taken over and I was past caring what was above or below me. Somehow I seemed to keep going, and finally Steve and I were out of the gorge and the world opened before us. We were looking at the Sanctuary.

The goddess showed off her many colours that night, as we camped near by the site called Patalkhan, which Shipton and Tilman had also used. The cloud that was drifting into the Sanctuary valley somehow stayed off the mountain face as it turned from pale gold to pink to a steely blue. Up close, we could see the ramparts of the West Face were so steep and overhung that only a light coating of snow could cling to the few ledges and sheer inward-sloping walls. We watched with awe. We had arrived.

As I stood in the heart of the Sanctuary, ringed by the cirque of mountains, I had come fully to appreciate Bill's dictum - that to get to there, it helped "to have a belief in something, anything, that endures".

|