|

Democracy in Nepal and the “international community” Manjushree Thapa

4 - 5 - 2005

A monarchist, military regime is crushing Nepal’s people. The rural Maoist insurgency offers them no hope. They deserve solidarity in their struggles to achieve democracy, says the Nepali writer Manjushree Thapa.

The international reaction following King Gyanendra’s military coup on 1 February 2005 has been mostly heartening for Nepalis. Until that date, we felt doomed to be characterised as simple, happy mountain folks inhabiting a Shangri-la, who deserved to be ruled by a deity-king, no matter how unjust. Maoist insurgency tended to be viewed as an anachronism, even fey: trouble in paradise. Meanwhile, Nepal’s real story – the decades-long (and continuing) struggle to establish and retain democracy – seemed destined to be overlooked. It was just not picturesque.

But the world’s condemnation of King Gyanendra’s military coup has made Nepalis feel that we are not being abandoned at this, the most traumatic and transformational era in our history. Still, Nepalis are wary about the international community’s trustworthiness, for any vestigial commitment to democracy in Nepal it has shown in the past has proved fickle.

In part this unreliability is because the outside world simply could not understand Nepal after democracy was won in 1990. It has been difficult enough for Nepalis to clarify this chaotic period even to ourselves. We were not prepared for the challenges of democracy. There were no democratic institutions, and very little democratic practice in either public or private spheres in 1990. The caste structure – with the Chettri, Bahun and “high-caste” Newar groups at the top – remained rigidly in place. It was widely felt that any move in the direction of equal rights for women would destroy Nepali culture. Any mention of ethnic rights could be met with accusations of harbouring separatist, anti-national, even treasonous sentiments.

A country in chloroform

This was the legacy of the closed, pre-1990 system. Political parties had been illegal, and could operate only underground. Free speech had been banned, and criticism punishable by law. No one could state their political position openly; communication took place either in tight circles, amid the fear of informers and infiltrators, or via secret messages embedded in public discourse.

In this paranoid atmosphere, political activists with liberal, socialist and (various) communist ideologies tended to remain segregated from and mistrustful of one another.

This stifling polity almost guaranteed that when their time came to govern, the parties would stumble. So it proved: when the ruling Nepali Congress Party abandoned socialism for capitalism under pressure from the World Bank and the IMF after 1990, the largest opposition party – the Communist Party of Nepal [United Marxist-Leninist, UML] – awkwardly tacked its old-style communism onto free-market economics without rejecting its strain of totalitarianism, as its Indian equivalents were to do. Nepali political parties did not worry at that stage about a comeback by monarchist and military forces, far less an unimaginable Maoist insurgency.

As a result of this unresolved adaptation to new realities, they muddled endlessly. In the early 1990s, one government after another fell to selfish power grabs, petty infighting and personality-based factionalism; corruption scandals proliferated; parliamentary sessions grew raucous even as street demonstrations, closures and strikes grew. All the major parties eventually split. The accumulated result was to block the progressive social and political reforms that Nepali people desperately needed.

Despite this, the democratic environment did allow lawyers, journalists, businesses and other professional groups to establish themselves. Unions, pressure groups and special interest groups formed. Activism flourished; among the new social movements were those campaigning for the rights of women, Dalit, ethnic groups, and gays.

Such fragile democratic institutions and practices had barely found their footing when the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) went underground and launched their armed insurgency in 1996. The Maoist demands were for an all-party interim government to be formed, followed by elections to a constituent assembly, and the creation of a new, republican constitution.

These demands had their roots in the 1940s, when republicanism had begun to grow and Nepali political parties were expressing aspirations to a new constitutional, democratic order. Fifty years on, however, the parties chose to be intimidated rather than inspired by the return of these aspirations in a new guise. To debate the demands seriously would require overcoming complacency and genuinely soul-searching for their own ideological commitments. It was so much easier to do what they did: move rightward.

As the Maoist insurgency escalated, Congress-UML governments enforced press censorship, suspended civil rights, and imposed a brutal counterinsurgency – eventually deploying the Royal Nepal Army – costing thousands of civilian lives. These parties passed the Terrorist and Disruptive Acts Ordinance, which made it possible to arrest people based merely on the suspicion that they were Maoists. In 2001 alone, more than 100 journalists were arrested. Amid vicious infighting and factionalism – intensified in the wake of the royal massacre of June 2001 – these parties moved from boycotting an entire session of parliament to eventually dismissing parliament without making the necessary preparations for elections in the war-torn countryside.

A friendless people

The machinations of the political parties caused a constitutional crisis in 2002, leaving King Gyanendra to take advantage. In October 2002 he dismissed the elected prime minister and established his own cabinet of handpicked palace loyalists. His ostensible purpose was to ease the crisis; he even cited Article 127 of the constitution in justification. This convinced very few Nepalis; people and press responded with street protests and strong denunciations against a return to monarchical rule. The king’s takeover was dubbed a “royal regression”.

But the international community – diplomats, and monetary and aid agencies – was greatly relieved. Political analysts have generally viewed Nepal’s travails as a standoff between three major powers: the king/military (or palace), the political parties, and the Maoists. Hari Roka, a political analyst, has added to this troika a fourth power: the international community, whose diplomats and aid industrialists supply more than 60% of the national budget and often hold more sway over Nepal’s governance than Nepalis themselves.

These representative individuals were often genuinely disgusted with the ineptitude of the democratic political parties, and concerned about the growing strength of the Maoist insurgency. But unlike Nepalis, they lacked any memory of life under absolute monarchy: somehow, in their minds, the king was a unifying force for Nepal. They threw their considerable weight behind him. India, the United Kingdom and the United States all welcomed his takeover. Aid, including military aid, continued and even grew.

So Nepalis were stuck with a king who had transgressed his constitutional remit. He dismissed cabinet after cabinet, all the while laying the grounds for his final ascendancy to power. This he achieved on 1 February 2005. Before that, he approached the embassies of the three “friendly” countries to gauge their reactions. They – or so they have latterly claimed – unanimously advised the king not to conduct a military coup.

But he did. And only then did it become apparent to the international community that in 2002 it had done no more than help the king buy time, and make the necessary preparations for 1 February 2005. To put it bluntly, the international community funded his military coup. Most complicit were India, the UK and the US, which together had supplied aid to the Royal Nepal Army despite its widespread and systematic human rights abuses.

It should have been an outrage to the taxpayers of these liberal-democratic countries that they were backing this dirty war. But it was not. Nepal was too far away, and its troubles were nebulous, obscure. So what if the king’s government did not release any expenditure reports since 2002? So what if the king’s salary increased hugely while many of his people were famished? So what if nobody knew how aid money was really being used? Only the Nepalis were outraged. But we did not matter.

This is why, despite the fact that India, the UK and the US all suspended military aid following the February coup, Nepalis remain suspicious of the international community. Aid is, after all, a cynical industry. There are jobs and contracts on the line for donor countries. The donor countries’ need to disburse aid is often greater than the recipient countries’ need to obtain it.

Democracy, moreover, is not the aid industry’s concern; in fact, democracy often deters the aid industry by forcing greater transparency and accountability in public expenditure. An old Nepal hand (who wishes to remain anonymous) voiced a common wariness to me when he said: “If this had been a competent fascist coup, they would have backed it. But it’s been an incompetent fascist coup. They’re embarrassed by how crude it is.”

King Gyanendra himself may pay lip service to the notion of democracy, but the army, or at least its top brass, have been openly contemptuous of the idea. It has targeted three groups for the worst repression: democratic political leaders, private media, and human rights activists. The military plan appears to be to silence all potential critics before going after the Maoists. This time, nobody will be able to speak out for the civilians who get in the way.

Nepalis’ fear now is that military aid might resume, helping to entrench military rule in Nepal. This is clearly what King Gyanendra hopes. Claiming that cutting off military aid only supports the Maoists, he has been lobbying hard for its resumption – at times begging before India, the UK and the US, at others threatening to ally with China, Pakistan, and even Cuba.

For a few days in late April it appeared that the king would be granted his wish, when the Indian government seemed ready to resume military aid. Indian security concerns over the Maoists were simply too strong, and the country’s military was pressing the New Delhi government. But India’s government was also opposed by its own left coalition partner and embarrassed by the continuing arrests of political activists in Nepal. Torn between these impulses, it waffled.

Whatever India does, the UK and the US will most likely follow. So far, the UK has generally given non-lethal aid to Nepal’s army, while the US has supplied lethal aid as well. But the supply of helicopters from the UK to Nepal shows how deceptive such categories can be: the Royal Nepal Army has conducted aerial bombing from helicopters for several years, targeting crowds heavily populated by civilians and a few Maoists. “Non-lethal”?

How can the world help Nepal?

What the international community must understand now is that if it resumes military aid, it will be actively helping the king derail Nepal’s democracy movement, and in time be held accountable for its betrayal.

If it does so, any appeal by the international community for the restoration of civil liberties, or even of democracy, will mean nothing. For once military rule is entrenched in Nepal, it will be near-impossible to return to developing democratic institutions and practice.

Since 1 February, the parties of the democracy movement in Nepal have been scattered and most of their top leaders are imprisoned, under house arrest, or underground. It is extremely hard to regroup under such conditions, but regroup the movement has.

The second- and third-tier cadres of all the parties are coming to the fore in two ways. First, they are voicing the demand for a new constitution via a constituent assembly, thus reclaiming an aspiration their parties had made as early as the 1940s, long before the Maoists appropriated it. Second, they are following the example of student party activists in the past who were often scorned for their advocacy of republicanism. This move is so far cautious, even nervous – for the monarchy looms larger in the lives and imaginations of older generations.

There is some disagreement as to how to form an all-party government. Some parties would prefer to re-establish the parliament that was dismissed in 2002; others prefer to establish a new all-party interim government. But for the most part, the political parties have by a different route reached the same view as the Maoists: Nepal needs a new constitution.

The parties have not overcome their ineptitude and indecision, but they are no longer intimidated by the scare of a return to absolute monarchy, of military rule. This conquest of fear obliges them to scale four new challenges: to throw up good leadership possessed of vision; to move beyond the immaturity that is a legacy of living for so many years underground; to sharpen their governance skills; and – most importantly – to bring the Maoists into a peaceful settlement via a new constitution.

All this can happen, albeit slowly, but only if the international community does not help the king and military to derail democracy before the opportunities can be seized. The king’s cautious release from prison of two leading communists, Madhav Kumar Nepal and Amrit Bohara, on 1 May is a small but significant step, reflecting the combination of internal opposition to the coup and external pressure.

Democracy is the only option for Nepal. This has been the main struggle for over seventy years. Nepalis are now regrouping to carry on the democracy movement, defying the severe repression and censorship imposed by the king and the military. They deserve support. The only action that the international community can take in good faith is to make a wager on the Nepali people and their democratic future. |

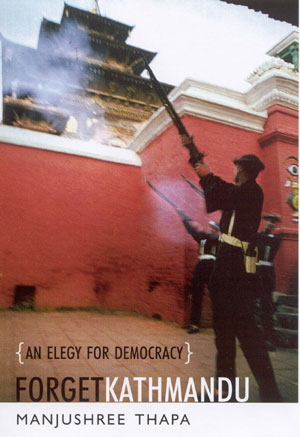

Forget Kathmandu

Forget Kathmandu